Congregational Life

Table of Contents

Members of Black faith communities asserted and expanded their freedom through worship, music, and many other activities. Faith communities were one of the few arenas for leadership and participation open to people of African descent. In the absence of schools, churches offered educational opportunities. Since Blacks could not freely visit restaurants, theaters, and other public venues, the church provided a comfortable setting where they could share a meal, enjoy leisure activities and entertainment, and develop friendships.

From their beginnings Black faith communities strongly opposed racism, slavery, and segregation. They denounced these practices as contrary to divine principles and the highest standards of human decency. The primary agencies of autonomy and self-help, churches and other faith communities became the central force in maintaining group cohesion and fostering self-respect under difficult circumstances. Their work can be viewed as an early expression of Black power.

Education

As Blacks became free, they recognized the importance of education for becoming productive, independent members of American society. Most Black churches offered Sunday school or day school, or both. In 1868, Wilmington’s five African American churches had over 400 students enrolled in Sunday school. Church-related educational activities provided religious instruction, basic education for literacy, and moral training for both children and adults. The concern for education is one of the ways in which Black churches took responsibility for more than the spiritual development of their members.

After the Civil War Delaware’s African Americans pushed for expanded educational opportunities. Along with the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Delaware Association (a white charitable organization), churches played a leading role in the effort. Churches often provided land for schools, and ministers sometimes taught when other teachers were unavailable.

Worship

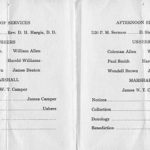

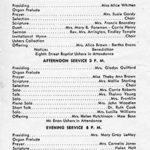

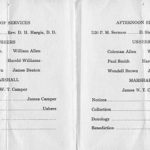

African American worship celebrates God’s love, care, deliverance, and liberation. It offers strength to survive daily struggles and courage to confront injustice. Services include scripture readings, singing, prayer, testimonies, and affirmations of faith. But the central focus of worship is the sermon, where the preacher proclaims the prophetic word of God, often challenging mainstream society. Within this basic framework, African American houses of worship offer many different worship experiences and traditions.

Music

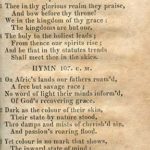

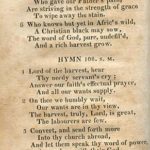

Music, in many different forms, is an integral part of African American religious life. Early worship featured spirituals, songs created spontaneously by Africans as they worked. Since the early 1900s, gospel music has been important. Throughout, traditional hymns have been sung as well. Today, African American churches embrace a wide range of musical expression.

This choir began in the church’s early days when an activity as simple and seemingly innocent as singing God’s praises was an act of assertion and liberation. According to the church’s 1934 Souvenir Booklet, “A splendid heritage has been left them by the valor of perseverance and patriotism of the men and women of the early Church who, though compassed about by hate, prejudice and the effect of abominable slave-laws yet in 1846, a few months after the Church was organized, these brave men and women joined and duly organized a Church Choir.”

This choir began in the church’s early days when an activity as simple and seemingly innocent as singing God’s praises was an act of assertion and liberation. According to the church’s 1934 Souvenir Booklet, “A splendid heritage has been left them by the valor of perseverance and patriotism of the men and women of the early Church who, though compassed about by hate, prejudice and the effect of abominable slave-laws yet in 1846, a few months after the Church was organized, these brave men and women joined and duly organized a Church Choir.”

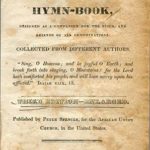

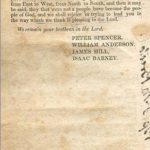

Peter Spencer, William Anderson, James Hill, and Isaac Barney chose these hymns from a variety of sources to reflect the spiritual needs and concerns of members of the African Union Church. As was the custom with all early hymnals, this one contains only words, and no music.

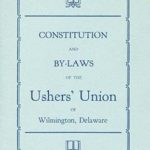

Ushering

Black churches have a long tradition of ushering as a ministry of service undertaken by committed men and women of all ages. Ushers learn a system of silent hand signals that ensures that the service runs smoothly and that any situations that may arise are taken care of unobtrusively. Ushers are also highly organized, both within individual churches and at the state level. In Delaware, four churches in Wilmington formed an Ushers Union in 1908. This grew into the Interdenominational Church Ushers Association of DE, which celebrated its centennial in 2008. The congregational and state organizations provide a strong foundation that enables ushers to provide many additional services to their churches and enjoy fellowship with each other.

Camp Meetings

Camp meetings—lively outdoor gatherings that combine faith, recreation, and socializing—have been part of Delaware’s religious landscape since 1805. As with other activities, Blacks were segregated at white camp meetings, so they started their own. Exactly when the first Black camp meeting in Delaware took place is unknown, but Jarena Lee preached at one in the Lewes area in 1824.

Nineteenth century camp meetings featured three or four services and sermons a day as well as music and prayer. The devout gathered under the bower to worship. Those not so devout socialized with friends and relatives, courted, played games, and even indulged in forbidden activities like enjoying alcoholic beverages.

At the earliest camp meetings, people camped in farm wagons covered with canvas. They later built simple cottages, still called tents. The tents circled the bower or arbor where services took place.

Despite their popularity, some people did not approve of camp meetings. They felt that the meetings did not really bring people to God or build up churches, and that inappropriate recreational activities received too much attention.

At one time, camp meetings—for both Blacks and whites—were spread throughout Delaware. Today, only a few African American camp meetings remain, attracting the faithful with their familiar blend of worship, fellowship, and recreation.

Frankford camp meeting, started in 1892 by Antioch A.M.E. Church (founded 1856), was one of the largest Black camp meetings in Delaware. In addition to activities in the campground, vendors of ice cream, candy, and other treats set up shop outside the grounds to capture the patronage of people in a holiday mood. In 1943, a fire destroyed the church and a number of tents. This view shows the bower and some of the tents that surrounded it. This camp meeting is still active.

Wesley camp meeting, still active today, started in the 1840s. Around 1865, two small frame building were erected on the site. One was used as the Blackwater Colored School for part of the year. This school continued, in various buildings, until 1951. Wesley Methodist Church was erected on the property in 1871, so the camp meeting is older than the church. The camp meeting, school, church, and cemetery, all on the same property, formed the center of the Wesley Community of Baltimore Hundred.

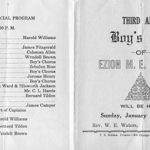

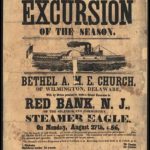

Fellowship

Fellowship is important for all faith communities, but especially for African Americans, who could not freely visit restaurants, theaters, and other places of amusement until recently. Faith communities provided a basis for organizing social and cultural activities that reflected their culture and values. Women often took the lead in planning and presenting fellowship activities.

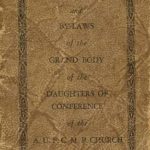

The Daughters of Conference, the main women’s group of the A.U.M.P. church, first organized in New York City in 1835. The Grand Body, the denominational organization, came together in Wilmington in 1861. The Daughters of Conference worked in many areas of church life and had a special interest in supporting retired clergy.

The continual round of building maintenance provides a source of service and fellowship. Zoar Methodist Church began in 1883 as Long’s A.M.E. Chapel. In 1924, the church building was moved to a new site and the new name was adopted. Zoar is still active.

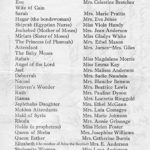

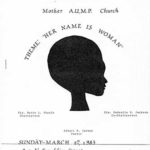

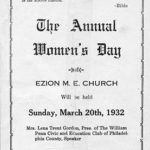

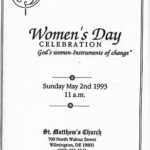

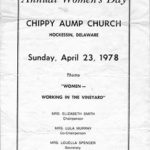

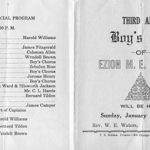

Since the early 1900s, women in many denominations have presented day-long events that feature worship led by women, fellowship, and fund-raising for church causes. Women’s day programs continue to be an important part of the annual calendar in many African American churches.

Bethel’s Rainbow Club, founded in 1928, presented pageants, recitals, socials, sacred concerts, and plays. The club had 71 members in 1934. One of its productions, “Great Women of the Bible,” presented at Mother A.U. Church, provides an example of interchurch cooperation in Wilmington’s close-knit African American community.

Cemetaries

In Delaware, segregation extended to the grave. Many white cemeteries did not serve Blacks or restricted Black burials to separate sections. As Black churches developed so did Black cemeteries. The earliest known African American burial ground in Delaware was the churchyard of Mother African Union Church on French Street in Wilmington. Since then, at least 60 Black cemeteries have been established, most of them associated with churches. They offered a place where African Americans knew they would be treated with respect, dignity, and comfort. Patterns of segregation in burial practices began to end in the late 1960s.

In Delaware, segregation extended to the grave. Many white cemeteries did not serve Blacks or restricted Black burials to separate sections. As Black churches developed so did Black cemeteries. The earliest known African American burial ground in Delaware was the churchyard of Mother African Union Church on French Street in Wilmington. Since then, at least 60 Black cemeteries have been established, most of them associated with churches. They offered a place where African Americans knew they would be treated with respect, dignity, and comfort. Patterns of segregation in burial practices began to end in the late 1960s.

Israel’s history dates to at least the early 1850s. The oldest stone in the graveyard is from 1854. The church shown here was built in 1916. The church and cemetery are both still active.

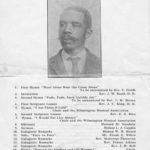

Michael Sterling’s funeral at Bethel A.M.E. Church in Wilmington, featuring ten ministers and two bishops, received extensive coverage in the Wilmington newspapers. Sterling served as a soloist, organist, and choir director at Bethel, in addition to other church activities. His talent and passion for sacred music, combined with his character and integrity, earned him great respect in the community. The Wilmington Musical Association, an organization of choirs from all of the African American churches, provided his tombstone, which reads as follows:

Israel’s Musician

Professor

M.T. Sterling

Feb. 15, 1859

Jan. 29, 1922

Founder of

Wilmington Musical

Association

1888

Sterling

Erected by W.M.A.

Rev. Henry J. Marshall, founding pastor of Union Missionary Baptist Church in Dover, purchased land for Lakeview Cemetery so that Blacks could have their own graveyard. He and his wife were buried there in 1935 and 1939, respectively. Unfortunately, their tombstones were vandalized and removed from their proper location. In winter 2013, when DelDOT was doing repair work under a bridge near Kenton, the tombstones were found and recovered. A new marker has been placed in Lakeview Cemetery, while the original tombstones have begun a new life as a means of education and memory.

Rev. Henry J. Marshall, founding pastor of Union Missionary Baptist Church in Dover, purchased land for Lakeview Cemetery so that Blacks could have their own graveyard. He and his wife were buried there in 1935 and 1939, respectively. Unfortunately, their tombstones were vandalized and removed from their proper location. In winter 2013, when DelDOT was doing repair work under a bridge near Kenton, the tombstones were found and recovered. A new marker has been placed in Lakeview Cemetery, while the original tombstones have begun a new life as a means of education and memory.

Rev. Henry J. Marshall, founding pastor of Union Missionary Baptist Church in Dover, purchased land for Lakeview Cemetery so that Blacks could have their own graveyard. He and his wife were buried there in 1935 and 1939, respectively. Unfortunately, their tombstones were vandalized and removed from their proper location. In winter 2013, when DelDOT was doing repair work under a bridge near Kenton, the tombstones were found and recovered. A new marker has been placed in Lakeview Cemetery, while the original tombstones have begun a new life as a means of education and memory.

Rev. Henry J. Marshall (1865 -1935), a native of Virginia, founded Union Missionary Baptist Church in Dover, first known as “The Little Mission,” in 1902. Fully aware of the needs of his people in a segregated society, Rev. Marshall provided more than spiritual leadership. He allowed pregnant women and their midwives to deliver their babies at the church, since the hospital was segregated. He also purchased the land for Lakeview Cemetery. In 1921, during a typhoid epidemic, Rev. Marshall spoke to the Dover city council about the need for better water and sewer systems. He led Union Church until his death.