Building Freedom

Table of Contents

The African American faith experience has always reached out into the larger world. As with all houses of worship, this comes from the mandate to spread the faith and save lost souls. But for Blacks, the lack of other avenues of involvement and expression made the church a center for advocacy on political and social justice issues as well. From Mother African Union Church hosting a meeting to protest colonization in 1831 to the modern civil rights movement and beyond, the African American faith community has been a focal point in the struggle for freedom and equality for all Americans.

Fighting Against Slavery

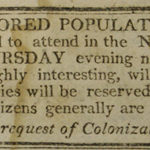

In the early 1800s, many whites who opposed slavery thought that free Blacks should return to Africa—a process called colonization. In July 1831, the colonization society invited Wilmington’s Blacks to a meeting–where they would sit in the balcony–to learn about colonization. In response, Blacks held a meeting at the African Union Church where they clearly expressed their opposition to colonization. They believed that it was not in their best interests and against the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Rev. Peter Spencer chaired the meeting, an early example of how the Black minister took on a leadership role that went beyond the purely spiritual.

To what extent did Delaware’s Black churches participate institutionally in the Underground Railroad? The lack of documentation makes it difficult to know. Individual members certainly were involved, drawing strength and purpose from their faith communities.

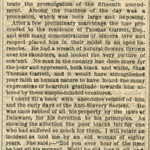

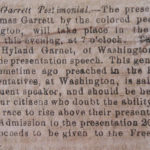

African Americans in Wilmington expressed their respect and affection for Thomas Garrett, Wilmington’s station master on the Underground Railroad, through their churches. After the 1848 trial that destroyed him financially, they held daily prayer meetings for him in their churches. In 1866, they gave him an engraved silver tray, on display in Distinctively Delaware in this museum, in a meeting at the “Brick church.” And when he died in 1871, a memorial service took place at Mother A.U. Church.

But very little is known about church involvement in actively helping freedom seekers. One church that has such a tradition is Star Hill A.M.E, in the Kent County African American community of Star Hill. Star of the East Church (which met in the building to the far left) was a safe place for freedom seekers and a site for anti-slavery meetings. Star Hill A.M.E. Church, founded in 1863 or 1866, was also a haven for escaping slaves.

Civil War and Reconstruction era

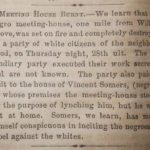

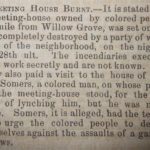

Sometimes the African American church confronts the world simply by its very existence. Such was the case on August 28, 1862, when a Black Methodist meeting house near Willow Grove in Kent County was burned by whites who were out to lynch Vincent Somers, on whose property the church stood. Somers, known in the community as a man who urged Blacks to stand up for their rights, was not at home at the time of the raid.

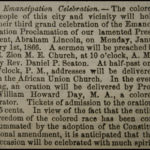

Black citizens held annual celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation, often in churches. In Wilmington in 1866, the morning observances took place at Ezion, while the afternoon session was at Mother African Union Church. Emancipation Day events continued for many years, offering a forum to celebrate achievements and continue the fight for full equality.

This convention, held at Whatcoat Methodist Church in Dover, was the first such gathering in Delaware. Rev. Theophilus G. Steward, the politically active pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church in Wilmington, organized the meeting. Delegates came from all over the state. Following the custom of the day, all were male. The meeting addressed many questions, but education and civil rights were the main topics. The delegates also voted in favor of abolishing the whipping post, a century before it actually was eliminated. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911), a leading abolitionist, lecturer, and author, addressed the convention and read one of her poems.

Civil Rights era

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., stayed overnight at the parsonage of Eighth Street Baptist Church (now The Resurrection Center) on North Clayton Street several times when his Crozer Theological Seminary classmate Rev. James L. Morgan lived there. One visit stands out. On September 12, 1960, King came to Wilmington to speak at Howard High School. After the program, others, including Rev. Maurice Moyer, joined the Kings and the Morgans for dinner at the parsonage and a lively discussion of civil rights issues.

On May 17, 1963, five ministers attending the annual conference of the A.U.M.P. Church in Wilmington staged a sit-in at Victoria’s Luncheonette at 12th and King streets. Victoria’s was the only restaurant that refused to sign the non-discrimination affidavit required to obtain a city business license.

The ministers, including Rev. George Brown, pastor of Mother A.U.M.P. Church and Rev. Sherman B. Hawkins of Star of the East Church in Newport, acted after Bishop Reese C. Scott and the entire conference declared their support of the NAACP’s campaign to end racial discrimination. They were arrested for trespassing, but the charges were dropped when a judge determined that they had been denied service solely because of race.

In the fall, a group called Concerned Citizens picketed the restaurant in a campaign sponsored by Mother A.U.M.P., Scott A.M.E. Zion, and Bethel A.M.E. churches. Victoria’s closed temporarily as a result of the picketing and reopened as a take-out place serving both Blacks and whites.

Rev. Brown, who was chair of the NAACP’s public accommodations committee, worked with Rev. Maurice Moyer on other sit-ins as well.