Wilmington 1968

The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land; confusion all around. That’s a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough can you see the stars. And I see God working in this period of the twentieth century in a way that men, in some strange way, are responding–something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee–the cry is always the same: “We want to be free.”

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” April 3, 1968

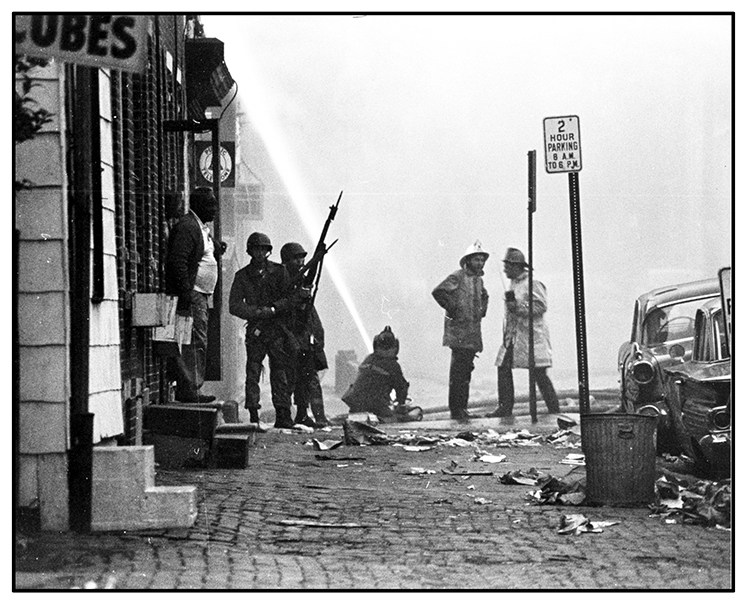

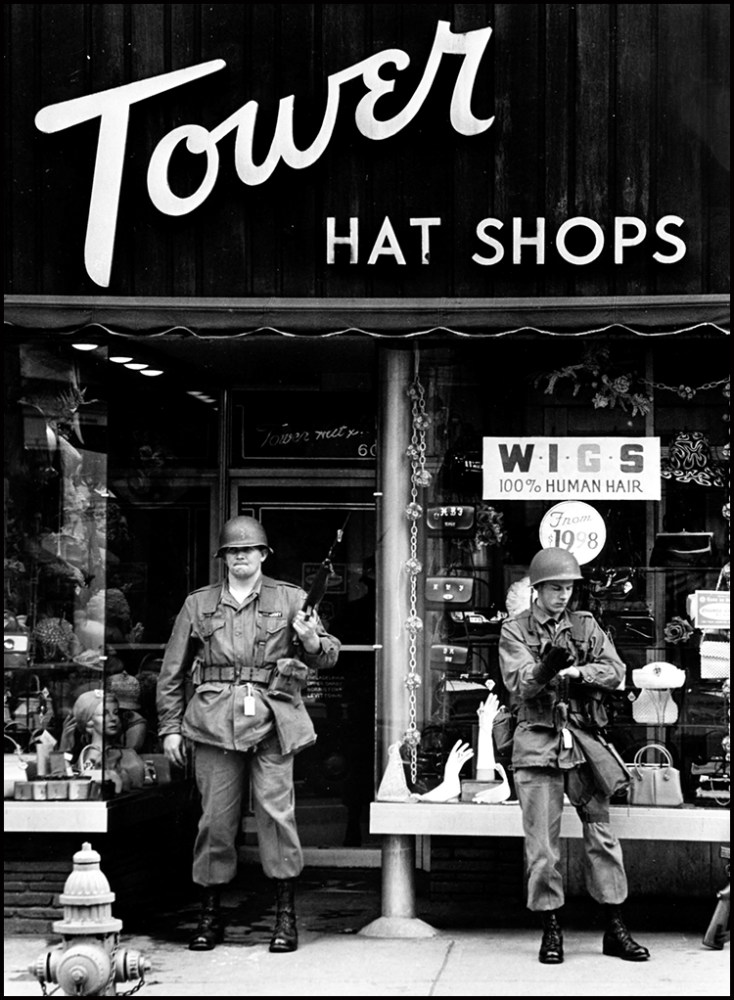

2018 marked the 50th anniversary of the civil disturbances that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. While demonstrations occurred in major cities across the country, Wilmington suffered through the longest occupation by the National Guard. Wilmington’s West Central City and Eastside neighborhoods were patrolled for nine months, from April to December. The military occupation exacerbated existing divisions of race and class, and the tensions of that time reverberate down to the present day.

The Delaware Historical Society and Mitchell Center for African American Heritage is proudly a part of the community-wide reflection, Wilmington 1968. This local series includes projects, exhibitions, and programs that remember the occupation and uprising in Wilmington and respond to critical issues facing the community today.

A world growing smaller, more connected by television and satellite communications, and more globally aware. Different nations in search of freedom from colonial powers were increasingly influenced by what was going on in the U.S., especially by the Civil Rights Movement, and in turn, the U.S. was influenced by what we saw going on in the world.

Young people, many of them college students, questioned authority, whether that authority took the form of university administrators, local police, or the federal government. The Civil Rights Movement provided a model of activism for student protesters to follow, and many of the veterans of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) returned to their campuses inspired to speak out against the Vietnam War and for women’s rights.

Rising body counts in Vietnam and increasing numbers of young men being drafted were draining the country’s resources away from Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, and the young people who protested in Wilmington were as aware of this fact as anyone else. As working class people who bore the burden of these shifts away from creating opportunities for jobs and education in their communities, they took matters into their own hands.

In Europe, the end of World War II and the Liberation was viewed as a missed opportunity to create a more open, less hierarchal society; similarly, returning Black World War II veterans were inspired to end racial segregation in American society, and their children channeled that energy into the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements. 1968 was a defining moment, nationally and internationally.

The civil disorder and unrest following King’s assassination in April was the expression of sadness of a people turned to anger, anger turned in on itself, and also turned out onto the streets, sparking fear in those who did not understand its deep-seated sources.In Washington D.C., in Boston, in Los Angeles, in Chicago, in other cities across the country, Black people expressed frustration with what they saw as a lack of change in American society, and in Wilmington, young people did the same.

This moment also sparked a renewed desire to work for change, a new generation of community activists who found direction in serving others and challenging the status quo. Rising youth movements implicitly understood the impact of media coverage to illustrate the conflict with police and underscore their higher moral position as non-violent protesters.

Even as Civil Rights Movement activists questioned the utility of the nonviolence philosophy, and began to disavow the accepted strategy, the ever-present tension created by the possibility of violence erupting on one or all sides was part of what made ongoing protests so powerful and compelling. A scholar and activist of the times, Julius Lester observed, “Thus, Black Power was merely the next step in a logical progression…It was new in the context of ‘the movement’ of the 1960’s. It was not new in the context of the lives of black people.”

![]()

As we reflect on this history, 50 years later, in Wilmington, we look at our society, and see men, women and children, still suffering, still struggling, still confronted with racism and discrimination and injustice and deprivation. We ask ourselves, how can this be? We ask ourselves, what can we do about this? How can we end poverty and gun violence? What can we do about homelessness in our society? How do we truly create a just society and a fair economy? How can we provide real, effective, and meaningful education for those who need it most?

The children of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements have children and grandchildren of their own, as do the college students who led protests against Vietnam on their campuses and in the streets. What future will those grandchildren make for themselves?