Preachers Of The Word

Table of Contents

The Black preacher or minister first emerged on American plantations as the African priest and medicine man. He became a unifying influence as enslaved Africans from many tribes sought to find solidarity as one people in America, speaking the same language and practicing essentially the same religion. Predating the Black church in America, he also became a symbol of hope and possibility, a boss, a healer, a prophet, a pastor. He gave voice to the pain, longings, hopes, dreams, and aspirations of an uprooted and oppressed people.

The Black preacher or minister came to prominence because the Black condition allowed few areas for leadership in the larger society. His caring function among his people extended into his roles as church founder and leader, civil rights activist, and educator. The minister’s functions have included not only the preaching, pastoral, and priestly dimensions but also the prophetic aspect. The Black preaching tradition has offered, and continues to offer, a critique of American values, tradition, and practices, which often moved from the pulpit into the political and social arenas.

Jarena Lee (1783-1849) of Philadelphia, the first woman authorized to preach in the A.M.E. Church, felt the call to preach in 1811. However, Richard Allen refused to give her permission. She persisted, and in 1819 Allen was so impressed by her that he gave her official standing. She traveled all over the U.S. and Canada, preaching to both white and Black congregations. Her travels brought her to Delaware several times. In 1823, she preached in Wilmington, New Castle, Christiana, St. Georges, Odessa, and Smyrna. The next year, she preached at an A.M.E. camp meeting in the Lewes area.

Peter Spencer and the African Union Church welcomed women as preachers even earlier, following the Quaker custom. The 1813 Discipline allowed both men and women to be licensed preachers, the lowest level of ordained ministry. Early women preachers in the Spencer tradition included Ferreby Draper, Araminta Jenkins, Annes Spencer, and Lydia Hall, who preached, taught, and offered pastoral care.

All of these women were pioneers in the long quest by women of all races to serve God as ordained clergy.

Religious Experience and Journal of Mrs. Jarena Lee, 1849: http://www.umilta.net/jarena.html

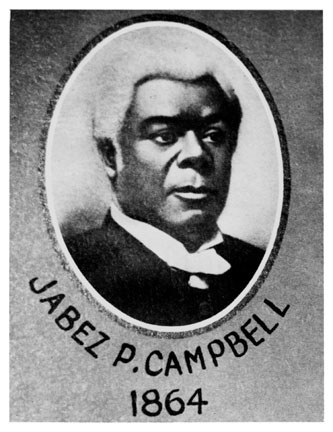

Bishop Jabez Pitt Campbell (1815-1891), born to free parents in Slaughter Neck, Delaware, ran away from home because his father gave him as collateral for a debt, making him subject to sale. He went to Philadelphia, where he was sold for a term of years but became free at the age of 18. Campbell became an A.M.E. minister in 1839, served at several churches in the mid-Atlantic region, and was elected bishop in 1864.

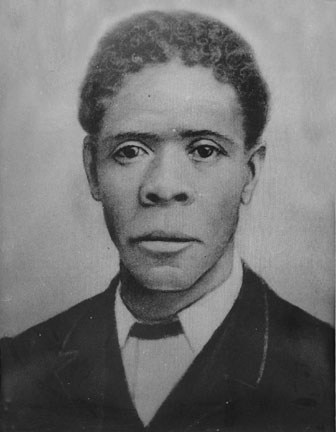

Rev. Edward Chippey (1825-1900) of Wilmington came from a family that had a long, active connection with the A.U.M.P. church. He was probably the son of Moses Chippey, one of the church’s founders. Chippey began preaching at a young age. He held various administrative posts in the church, founded several churches, and was a leader in Wilmington’s Black community. Chippey Street in Wilmington is named for him, as is Chippey Chapel in Hockessin.

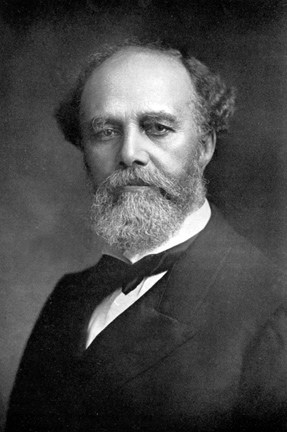

Rev. Theophilus G. Steward (1843-1924), a native of Gouldtown, New Jersey, began his career as an A.M.E. minister as a missionary in Reconstruction-era South Carolina and Georgia from 1865 to 1872. In 1872, he became pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church in Wilmington. Steward soon became active in Republican politics, with a special interest in education for Blacks. In late 1872, he issued a call for the first Black convention in Delaware, which met at Whatcoat Methodist Church in Dover in January 1873. Shortly after this Steward briefly served as a missionary in Haiti, but returned to Sussex County in fall of 1873. There he served churches in Milford, Milton, Slaughter Neck, Georgetown, and Lewes for a year. After several other pastorates, he returned to Bethel in Wilmington for a few years in 1881. Continuing his interest in education Steward spoke out in favor of integrated classrooms, a divisive issue among Blacks. After leaving Wilmington, he had several other pastorates, served as a U.S. Army chaplain from 1891 to 1907, and finished his career teaching at Wilberforce University in Ohio.

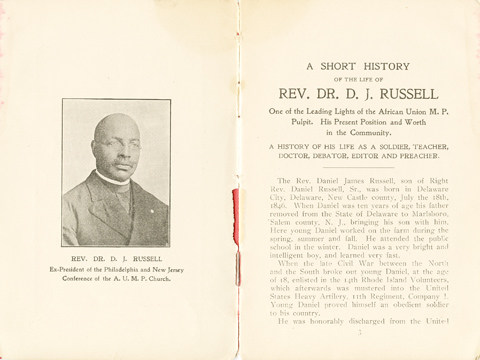

Rev. Dr. Daniel J. Russell (1846-after 1922), son of an A.U.M.P. minister, grew up in Delaware City and served in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. He taught school in Summit Bridge, Delaware, learned the shoemaker’s craft, and became a doctor. Russell was a minister in the A.M.E. Zion church before returning to the A.U.M.P. denomination. He served as pastor of churches in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and Wilmington and held denominational leadership positions. Russell also published The Union Star, the denomination’s first periodical, operated the Afro-American Book Store in Philadelphia, ran Russell’s Bible Training School in Philadelphia, and wrote History of the African Union Methodist Protestant Church (1920).

Bishop Levi J. Coppin (1848-1924) grew up in Cecil County, Maryland. He lived in Wilmington and Smyrna, Delaware, from 1869 to 1877, working at various jobs while being very active in the A.M.E. congregations in both places. He was licensed to preach at Bethel A.M.E. in Wilmington in 1877 and entered active ministry. Coppin served at various churches, held denominational leadership posts, and was elected bishop in 1900. He spent several years in South Africa in the early 1900s.

Unwritten History, Levi Jenkins Coppin, 1919: http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/coppin/coppin.htm

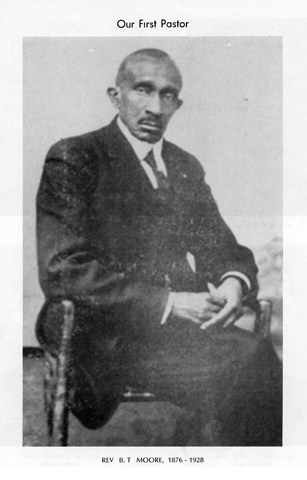

Rev. Benjamin T. Moore (1863-1928), a native of Charleston, West Virginia., and a student at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., came to Shiloh Baptist Church as its first pastor in 1876. A modest and unassuming man, Moore led Shiloh for over 50 years, taking it from infancy to a large and influential congregation.

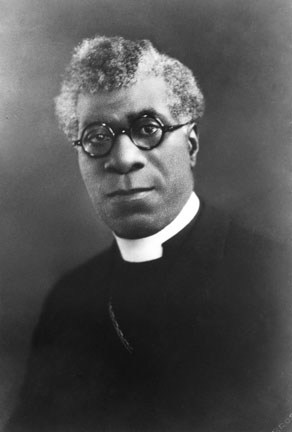

Bishop Thomas Demby (1869-1957) grew up in Wilmington, attending Eddy Anderson’s private high school for Blacks housed at Ezion M. E. Church. He then left to pursue higher education and an early career in education and possibly the A.M.E. ministry. Ordained an Episcopal priest in 1899, Demby served Black churches in various states. In 1918, he was elected the first African American suffragan (assistant) bishop in the United States “for Colored Work in the Diocese of Arkansas and the Province of the Southwest.” Throughout his career he fought discrimination to bring Blacks to the Episcopal church.

Rev. A. Chester Clark served at Bethel A.M.E. Church in Wilmington from 1933 to 1939. According to Bethel’s 1934 Souvenir Booklet, he was a “Human Dynamo, Excellent service: Doctrinal sermons, keeping pace with the times….Keeps our Church crowded with enthusiastic followers.” After the fire that destroyed Bethel on January 1, 1935, Clark provided the courage and leadership that allowed the congregation to rebuild.

Bishop Charles W. Thomas (1896-1967) was the youngest man to become a bishop of the Church of the Living God, a Holiness or Pentecostal denomination. He was bishop in Delaware and Maryland. He came to Delaware after serving churches in Connecticut and Baltimore. In Wilmington, he was pastor of the Church of the Living God at Ninth and Spruce streets. He also worked as a bricklayer and helped build P.S. du Pont School in Wilmington. Revered as a great preacher, Bishop Thomas attracted hearers from miles around.

A native of Georgia, Bishop Quintin Primo (1913-1998) was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1942 after an early career in education. He came to St. Matthew’s Church in Wilmington in 1963. Under his leadership, the church attained parish status and established community job-training programs before he left in 1969. In 1972 Primo was elected suffragan (assistant) bishop of the Diocese of Chicago. When he retired in 1985, he returned to Delaware as interim bishop and remained here. Primo had a lifelong commitment to equality and justice for all that he acted on in both the Episcopal church and the communities that he served.

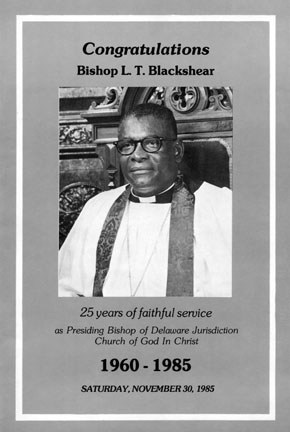

Bishop L.T. Blackshear (1916-2008) came to Delaware from the South in the 1940s to serve as a minister in the Church of God in Christ (C.O.G.I.C.). He began as assistant pastor of Gethsemane Church, then became pastor of Mt. Calvary Temple C.O.G.I.C. in Wilmington. When he became superintendent of the Southern district, C.O.G.I.C. began to grow in Delaware. Rev. Blackshear was appointed bishop of Delaware in 1960, a post he held until his death. During his career, C.O.G.I.C. in Delaware grew from three to 18 churches. Bishop Blackshear was revered in Delaware and nationally for his faith, pastoral care, leadership, principles, and willingness to confront violence and work for peace.

Rev. Maurice Moyer (1918-2012), a native of Chattanooga, Tennessee, and a graduate of Lincoln University Theological Seminary, came to the Wilmington area in 1952 to start a Presbyterian church for Blacks. Focusing his efforts in Dunleith Estates, he recruited the founding members of Community Presbyterian Church, which was chartered in 1955. Moyer played a leading role in the civil rights movement in Delaware, serving as president of the Wilmington Branch of the N.A.A.C.P. during the key years of 1960-1964. In 1963, he served as the first Black moderator of the New Castle Presbytery. Moyer also held several positions in the field of education and served on community boards. He retired from Community Presbyterian Church in 1998, revered as the dean of Delaware’s Black clergy.